Critics say the change in policy may be illegal

The mental health experts who help decide whether convicted sex offenders are too dangerous to be released from custody used to rely heavily on face-to-face interviews.

They would travel to the prison, sit across a desk from the inmate in a tiny office and ask deeply personal questions about parents, siblings, puberty, sex. Many say it’s the best way to understand what makes someone tick.

Now the experts are more likely to sit at home and look at an inmate’s records on a computer screen.

That shift in policy may be illegal, critics say. It has prompted a local assemblyman to ask for a government audit and has raised concerns about the effectiveness of a program designed to protect the public from what are known formally as sexually violent predators.

“It’s gone from a very well-functioning program to just a disaster,” said a sex-offender evaluator who has worked on the program since its inception in 1996. She asked to remain anonymous for fear of losing state contracts. “The whole program is in disarray.”

Nancy Kincaid, a spokeswoman for the state Department of Mental Health, which runs the Sex Offender Commitment Program, denied that the new policy is illegal or that it has affected the quality of the evaluations. She said about 40 percent of the inmates refuse to be interviewed anyway.

Questions about the program are mounting in the wake of the slayings of Chelsea King, 17, of Poway and Amber Dubois, 14, of Escondido.

John Albert Gardner III, 30, a convicted sex offender, is charged with raping and killing Chelsea and is a focus of the Amber investigation. He has pleaded not guilty.

Critics say the commitment program is overwhelmed by Jessica’s Law, a crackdown on sex offenders approved by voters in November 2006.

The measure brought a tenfold increase in referrals from the prisons for psychological evaluations. But the number of offenders being sent to mental hospitals rather than being released has gone down, according to a data analysis by The San Diego Union-Tribune.

Now some people want to know why.

“The state’s management of sex offenders has failed countless children over the years. This has to stop,” said Assemblyman Nathan Fletcher, R-San Diego, whose district includes Chelsea’s family. He’s calling for a Bureau of State Audits investigation.

Fletcher’s concerns echo earlier complaints lodged by a San Francisco lawyer representing a group of private-contract psychologists and psychiatrists. They say they’re being pressured by program administrators to do cursory evaluations as a way to save money.

Commitment programs began in Washington state in 1990 and have spread to 20 states. California’s began in 1996.

The programs have always been controversial, flying in the face of America’s notion of itself as a land of liberty by locking up people for crimes they might commit.

The programs are expensive, too — roughly four times as costly as prison.

But they’re also popular with a public outraged by repeat offenders, and they’ve withstood legal challenges all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court.

California’s program requires prison officials to red-flag sexually violent inmates when they’re nearing parole and refer them to the Department of Mental Health for an evaluation by two psychologists or psychiatrists.

A traditional evaluation involves a review of case files, an interview with the inmate in prison and a written report — a process that typically takes 20 to 30 hours, evaluators say.

If the evaluators disagree about an inmate’s prognosis, two more clinicians are brought in. If they also disagree, the offender is paroled.

That, in essence, is what happened with Gardner, although under a different program for mentally disordered offenders. Evaluators disagreed about the threat he posed after his 2000 conviction for molesting a 13-year-old neighbor, and he was released.

Inmates found to be a continuing danger are sent to court in the county where they were last convicted.

A judge or jury decides whether an inmate should be hospitalized.

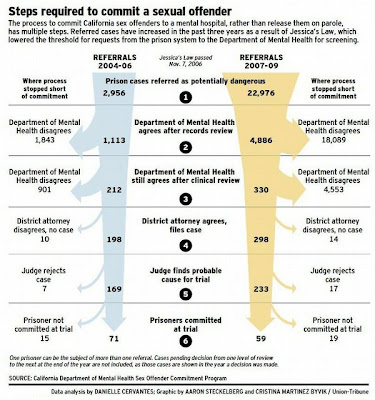

In 2004 through 2006, there were 2,956 referrals from the prison system for Department of Mental Health evaluations, an average of 82 per month. In that same period, there were 71 commitments.

Jessica’s Law widened the net in late 2006. Only one offense was required to qualify for screening, instead of the previous two. And the number of sex crimes that triggered review grew from nine to 35.

As a result, there were 22,976 referrals in 2007 through 2009, an average of 638 per month. During those three years, there were 59 commitments.

Despite the huge increase in prison referrals, then, commitments have gone down. Why? The Union-Tribune data analysis shows that the rate of cases moved forward by prosecutors and judges has stayed the same, with less than 10 percent of cases rejected.

But the rate of rejection by the Department of Mental Health has gone up significantly.

Before Jessica’s Law, 62 percent of referrals were eliminated in an initial screening. Since then, it has been 79 percent.

Before Jessica’s Law, 81 percent of cases were rejected after the next step, a full evaluation including an interview. Since then, it has been 93 percent.

Kincaid said the rejections went up because many of the new referrals don’t have an underlying mental disorder and a propensity for sexual violence that would qualify them for commitment.

But critics say the program is weeding out more cases at the front end, both to better manage the increased workload and to save money.

The initial screening used to include just a check of whether the inmate had committed a qualifying crime. In 2007, deeper record reviews were added. They call for scrutiny of an inmate’s case files, but no face-to-face interviews, and generally take a few hours.

“We were told it was legal, and if we didn’t do it, some evaluations wouldn’t get done at all, and nobody wants that to happen,” the longtime evaluator said. “We figured it was better than nothing.”

Chris Johnson, the San Francisco lawyer who represents some evaluators in a potential whistle-blower lawsuit against the state, questions whether the change is legal.

He pointed to the state code that governs the program, which says that once a referral comes to the Department of Mental Health, two psychologists or psychiatrists are supposed to do a “full evaluation.” For most professionals, a full evaluation includes an interview, Johnson said.

But Kincaid referred to another code section that calls for a review by prison officials of an inmate’s “social, criminal and institutional history.” Because of its expertise, the Department of Mental Health does that, which is where the record reviews come in, she said.

Johnson said evaluators who refuse to do record reviews on ethical grounds face a backlash. The evaluator said there’s pressure from department administrators to find that an inmate isn’t dangerous.

Kincaid called those allegations “patently false.” She said evaluators are encouraged to get whatever records they need to render an opinion and, if in doubt, can pass an inmate along to the next level of scrutiny, which includes interviews.

The evaluator acknowledged that she stands to gain financially if the program returns to more full evaluations and fewer record reviews. Some did very well under the old system.

In the first year after Jessica’s Law passed, the program raised the flat rate for evaluations from $2,000 to $3,500 to entice the 70 private-contract experts who perform them to do more and reduce a backlog.

About a dozen of them ended up making more than $500,000 that year, and at least one made more than $1 million.

The latest contract still pays about $3,000 for clinical evaluations. The flat rate for a record review is $75.

Staff data specialist Danielle Cervantes contributed to this report. John Wilkens: (619) 293-2236 begin_of_the_skype_highlighting (619) 293-2236 end_of_the_skype_highlighting; john.wilkens@uniontrib.com